When you sign a contract-whether it’s buying a business, hiring a software vendor, or outsourcing manufacturing-you’re not just agreeing to exchange goods or services. You’re also agreeing to take on risk. And that’s where liability and indemnification come in. These aren’t just legal buzzwords. They’re the real-world safety nets that decide who pays when things go wrong.

What Indemnification Actually Means

Indemnification is a promise in a contract that one party will cover the other’s losses. It’s not vague. It’s specific. If your software vendor’s code causes a data breach, and your customers sue you, an indemnification clause says: “I’ll pay your legal fees, settlements, and any fines.” That’s not charity. That’s risk transfer.

The term comes from common law, but today it’s standard in nearly every commercial deal. Think of it like insurance-but private, negotiated, and written into your contract. Cornell Law School defines it simply: “To indemnify means compensating a person for damages or losses they’ve incurred.” That’s it. No legalese. Just money moving from the party who caused the problem to the one who got hurt by it.

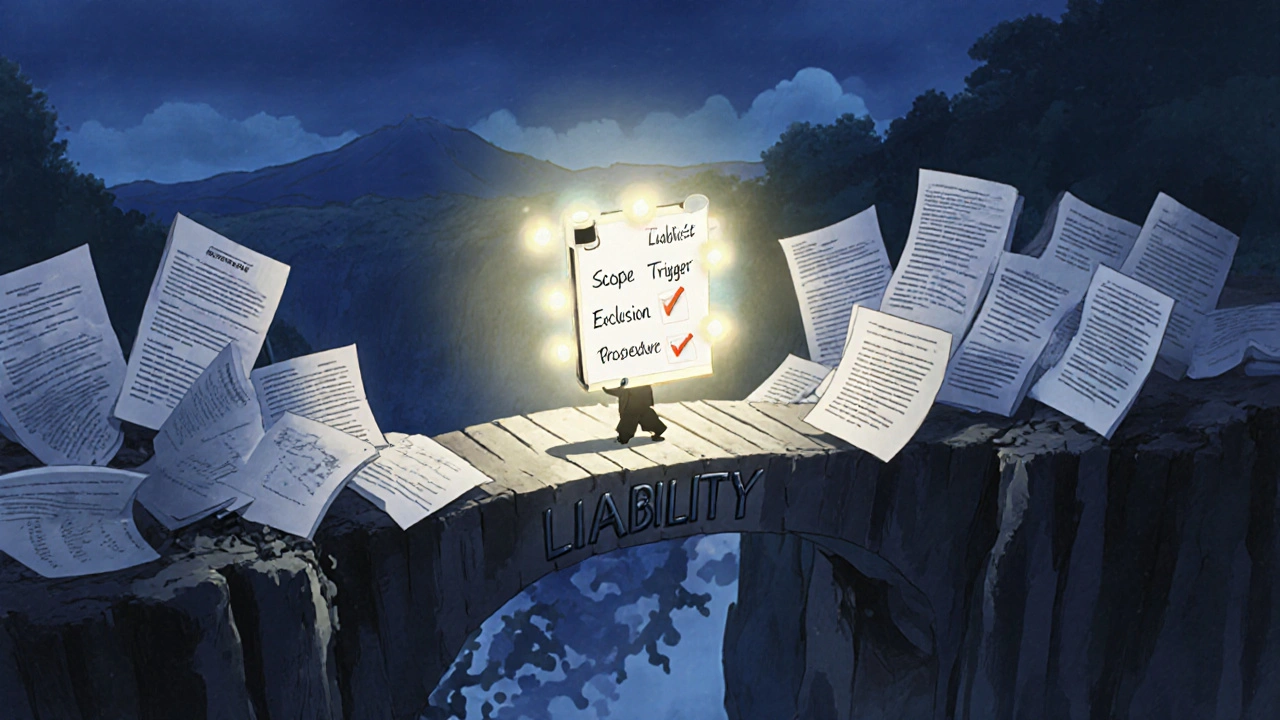

The Seven Parts of a Strong Indemnification Clause

A weak indemnification clause is worse than none at all. It creates confusion, delays, and lawsuits. A strong one has seven clear parts:

- Scope of Indemnification - What exactly is covered? Legal fees? Third-party claims? Regulatory fines? Tax penalties? If it’s not listed, it’s probably not covered.

- Triggering Events - What makes the obligation kick in? Breach of contract? Negligence? Intellectual property infringement? You need to spell out the exact events.

- Duration - How long does the protection last? Some clauses expire when the contract ends. Others survive for years-especially for things like tax liabilities or environmental damage.

- Limitations and Exclusions - No one pays for everything. Most contracts exclude indirect damages (like lost profits) or punitive damages. Caps on total payouts are also common.

- Claims Procedure - You can’t just send a bill. You have to notify the other party in writing, usually within 30 days. Missing the deadline? You might lose your right to claim.

- Insurance Requirements - Does the indemnifying party have to carry insurance? If so, what kind? General liability? Cyber liability? For how much? This ensures they can actually pay if called on.

- Governing Law and Jurisdiction - If there’s a fight, where does it happen? Which state’s laws apply? This avoids costly forum shopping.

These aren’t optional. Skipping any of these turns indemnification from protection into a gamble.

Indemnify, Defend, Hold Harmless - What’s the Difference?

People use these terms like they’re the same. They’re not.

- Indemnify means: “I’ll pay you for losses you suffer.”

- Defend means: “I’ll hire your lawyers and pay for your court costs.”

- Hold harmless means: “You can’t sue me for anything related to this, even if you messed up.”

That last one is tricky. If you’re the buyer and the vendor says “hold harmless,” they’re trying to lock you out of suing them-even if your own actions caused the problem. Courts often interpret “hold harmless” as redundant if “indemnify” and “defend” are already there. But in some states, it’s treated as a separate obligation. Don’t assume. Read it.

California case law (Crawford, 44 Cal. 4th 541) confirms: “Indemnify” means paying for legal liability. “Defend” means paying for the fight. Don’t mix them up in your contract.

Mutual vs. Unilateral: Who Pays Whom?

Not all indemnification is equal. There are two main types:

- Unilateral - One party pays the other. Common in vendor-customer deals. For example, a software company indemnifies its client if the software violates someone’s patent. The vendor has control over the product, so they take the risk.

- Mutual - Both sides protect each other. Typical in joint ventures or construction contracts. If a subcontractor gets hurt on site, both parties might cover each other’s liability. It’s fairer, but harder to negotiate.

In M&A deals, sellers almost always indemnify buyers. Why? Buyers are taking over the business and don’t want surprises. Sellers, on the other hand, fight hard to limit their exposure. They’ll push back on broad language like “any claim related to the business.” Instead, they’ll demand: “Only claims tied to breaches of the specific representations we made.”

Fundamental vs. Non-Fundamental Representations

Indemnification often ties back to what’s called “representations and warranties.” These are promises made in the contract about the state of the business or product.

Fundamental reps are the big ones: ownership of assets, legal authority to sign the deal, no hidden liabilities, tax compliance. These usually carry longer survival periods-sometimes 3 to 5 years after closing.

Non-fundamental reps are the details: employee benefits, IP licenses, minor contracts. These often survive only 12 to 18 months.

Why does this matter? Because indemnification kicks in only if one of these promises turns out to be false. If the seller said “we own all the IP,” but they licensed part of it from a third party without telling you-that’s a breach. And if that causes a lawsuit? The seller pays.

Survival Periods, Caps, and Deductibles

Even if you have a solid indemnification clause, sellers won’t leave you with unlimited exposure. That’s where three negotiation points come in:

- Survival period - How long after closing can you still make a claim? Shorter periods favor sellers. Longer ones favor buyers.

- Deductible (or basket) - The first $50,000 in losses? You cover it. Only after that does the seller pay. This prevents small claims from triggering indemnification.

- Cap - The maximum the seller will ever pay. Often set at 10% to 50% of the deal value. For high-risk industries, it might be higher.

These aren’t just legal jargon. They’re real financial brakes. A $10 million deal with a $1 million cap and a $100,000 deductible means the seller’s risk is capped at $900,000. That’s manageable. Without them? You’re asking for bankruptcy.

Insurance: The Safety Net Behind the Safety Net

What good is a promise to pay if the other party is broke? That’s why insurance requirements are non-negotiable in serious deals.

Indemnification clauses often require the indemnifying party to carry:

- General liability insurance

- Professional liability (E&O)

- Cyber liability insurance

- Directors and Officers (D&O) coverage

And they must provide proof. Not a quote. Not a brochure. A current certificate of insurance naming the indemnitee as an additional insured. If they can’t produce it, the deal should pause. No exceptions.

Real-World Example: The Data Breach

Imagine you buy a customer database from a third-party vendor. Six months later, hackers steal the data. Your customers sue you for $2 million in damages and notification costs.

Your contract says: “Vendor shall indemnify Buyer for losses arising from breach of data security obligations.”

Now you send a formal notice. You attach the lawsuit, the breach report, and your legal bills. The vendor’s lawyer reviews it. They confirm the breach was due to their outdated firewall. They accept responsibility. They pay your legal fees. They cover the $1.8 million in customer payouts. They even pay for credit monitoring.

That’s indemnification working as designed.

Now imagine the clause said: “Vendor will indemnify for third-party claims only if caused by intentional misconduct.” Now you’re stuck. The breach was negligence, not intent. No payment. You lose millions.

That’s why wording matters.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Here’s what goes wrong in 8 out of 10 contracts:

- Too broad - “Indemnify for any claim related to this agreement.” Courts hate this. Narrow it to specific breaches.

- No notice requirement - If you wait six months to tell them about a lawsuit, they can refuse to pay.

- Missing insurance - No proof of coverage? You’re trusting a paper promise.

- Ignoring governing law - California law treats indemnity differently than New York. Know which one applies.

- Assuming “hold harmless” means something new - It usually doesn’t. Just focus on indemnify and defend.

Fix this by using a checklist. Every time you draft or review a contract, run through the seven elements. If one’s missing, push back.

Bottom Line: Indemnification Is About Control

Indemnification isn’t about fairness. It’s about control. Who controls the risk? Who controls the defense? Who controls the money?

Buyers want maximum protection. Sellers want to limit exposure. The middle ground is where deals get done.

Don’t let your lawyer copy-paste a clause from last year’s deal. Every transaction has unique risks. Your indemnification clause should reflect that.

And if you’re signing a contract without understanding these terms? You’re not signing a deal. You’re signing a lottery ticket.

What happens if the indemnifying party goes bankrupt?

If the party responsible for paying indemnification goes bankrupt, you may not recover anything unless they had insurance or assets secured by a lien. That’s why insurance requirements and collateral clauses are critical. Always require proof of coverage before closing.

Can indemnification cover punitive damages?

Usually not. Most contracts explicitly exclude punitive damages because courts often refuse to enforce them under indemnity clauses. Always check the exclusions section. If it’s not listed, assume it’s excluded.

Do I need a lawyer to draft an indemnification clause?

Yes. Indemnification clauses are among the most litigated parts of contracts. A poorly worded clause can cost you millions. Even if you’re using a template, have an attorney review it for scope, triggers, and jurisdiction.

Is indemnification the same as insurance?

No. Insurance is a third-party policy that pays out based on coverage terms. Indemnification is a contractual promise between two parties. Insurance often supports indemnification, but it doesn’t replace it.

Can I waive indemnification entirely?

Technically yes, but it’s rare and risky. In most commercial deals, especially M&A or tech contracts, buyers won’t proceed without some level of indemnification. Walking away from it leaves you exposed to unknown liabilities.

13 Comments

indemnify? more like indemnify-later-when-we-get-around-to-it. seen too many contracts where this clause is just window dressing. vendor says they’ll cover it, then goes ghost after the breach. no insurance proof? no deal. simple.

I’ve been on the receiving end of a bad indemnity clause and it nearly broke my company. Not because of the breach-but because the vendor’s lawyer made us jump through 17 hoops just to submit a claim. Read the fine print. Don’t assume it’s fair. It’s not.

Let me tell you something about indemnification from the trenches-when you're the vendor in India supplying software to a US client, you’re always on the back foot. They want unlimited liability, no caps, full defense, insurance certificates, jurisdiction in Delaware, and a signed affidavit from your grandmother. But here’s the truth: if you give them everything, you’re signing your own death warrant. I’ve learned to negotiate hard. I cap indemnity at 150% of contract value, exclude punitive damages, require cyber liability insurance with $5M coverage, and make the survival period 18 months max. Anything more? I walk. I’ve lost deals this way, but I’ve never lost my company. You don’t protect yourself by being nice. You protect yourself by being precise.

Wait so ‘hold harmless’ isn’t magic? I thought that meant I couldn’t be sued at all. So it’s just redundant? That’s wild. I’ve seen lawyers slap that in like it’s a shield. Turns out it’s just extra words.

Actually, in Indian contract law, ‘hold harmless’ has been interpreted differently under Section 124 of the Indian Contract Act-it’s not always redundant. Courts have treated it as a broader obligation than indemnification alone, especially when combined with ‘defend.’ You’re oversimplifying. This isn’t just American law. The post ignores global context. Also, ‘indemnify’ doesn’t always mean ‘pay’-sometimes it means ‘reimburse after the fact,’ which changes everything. You need to check the jurisdiction. Not everyone operates under California law.

Indemnification… is not… a ‘safety net’-it’s a psychological contract… a silent war… waged in legalese… between fear and control… You think you’re buying software? No… you’re buying a liability… wrapped in a promise… written in ink… that may or may not… be enforceable… depending on… whether… the indemnifier… is solvent… or… just… good… at… paperwork…

There’s a quiet beauty in a well-crafted indemnity clause-it’s like a handshake that outlives the handshake. It’s not about distrust. It’s about honoring the fact that things go wrong, and we’re still human enough to say, ‘I’ll help you fix it.’ The real tragedy isn’t the breach-it’s when we treat contracts like weapons instead of bridges.

So… you’re telling me if I don’t have a lawyer, I’m basically signing a lottery ticket? Cool. So the whole post is just a sales pitch for lawyers. Thanks for the insight, captain obvious.

Let’s be real-90% of these indemnity clauses are garbage. Vendor says ‘we’ll indemnify’ but has $20k in assets and no insurance. Client signs it anyway because they’re in a rush. Then they cry when the breach happens. This isn’t legal advice-it’s a warning label for people who don’t do due diligence. You want protection? Do your homework. Don’t rely on a clause written by someone’s cousin who took a law class in 2012.

Y’all are overcomplicating this. If you’re doing business in the U.S., you need indemnification. Period. No exceptions. If the vendor can’t provide cyber liability insurance with a $10M limit? They’re not qualified. End of story. We don’t play around here. This isn’t some third-world contract negotiation. We have standards. And if you can’t meet them? Go work for someone else.

Just had a client get burned by this exact scenario. Vendor had indemnity clause but no insurance. Breach happened. Vendor vanished. Client lost $1.2M. We went back and added a ‘collateral clause’-now we require escrow of 10% of contract value as security. Also, always get the insurance certificate. Not the quote. Not the email. The actual certificate. Signed. Dated. Valid. It’s the difference between hope and proof. And yes, I’m a lawyer. And yes, I still get mad about this stuff.

Yeah, this is solid. Just remember-if they won’t give you insurance proof, they’re not worth your time. Simple as that.

There is no excuse for using the phrase 'lottery ticket' in a legal context. This post is riddled with informalities, inaccuracies, and emotional language. Indemnification is a precise legal mechanism-not a metaphor for gambling. You’ve misled readers by conflating risk with chance. A contract is not a game. It is a binding instrument. And if you don’t treat it with the gravity it deserves, you deserve to lose.

Write a comment