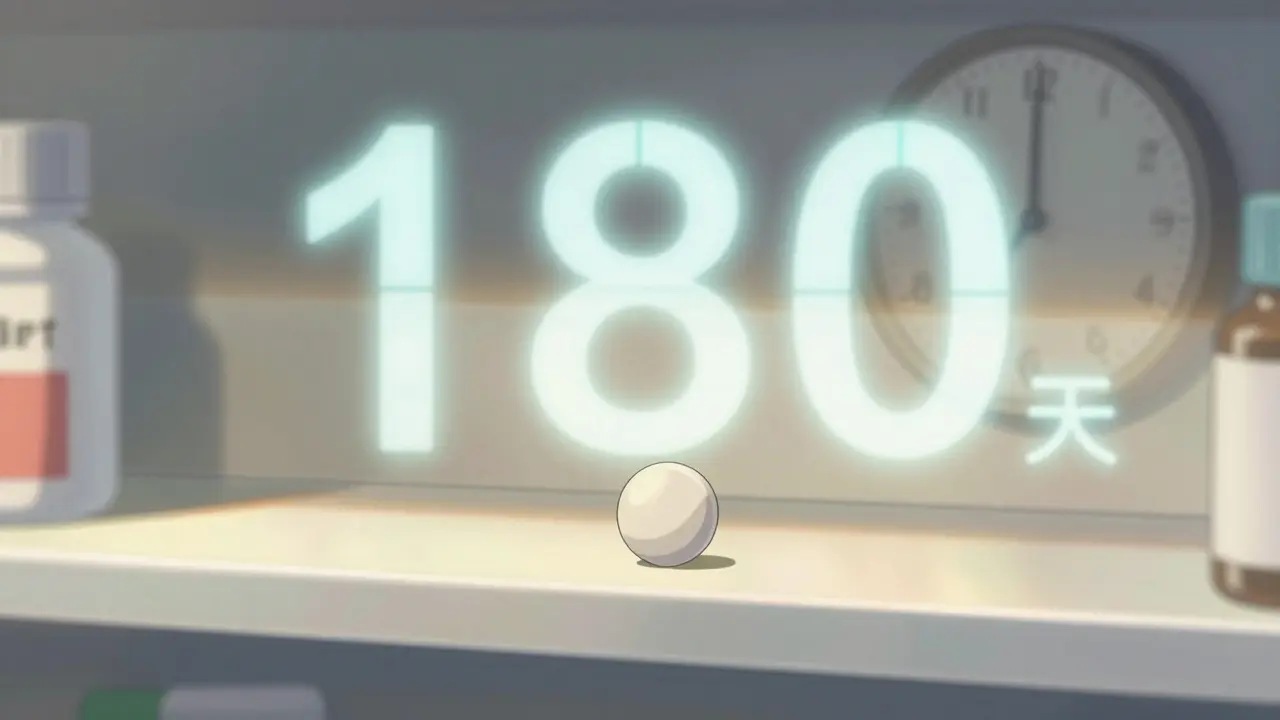

When a brand-name drug loses patent protection, it doesn’t just open the door for one generic competitor-it triggers a chain reaction. The first generic to hit the market gets a 180-day window of exclusive sales under the Hatch-Waxman Act. During that time, it captures 70-80% of the market, selling at 70-90% of the brand’s price. That’s not just profit-it’s a lifeline. Developing a generic drug and fighting a patent lawsuit can cost $5-10 million. The first entrant needs that exclusivity to break even.

But then, everything changes.

As soon as that 180-day clock runs out, other companies rush in. And when they do, prices don’t just drop-they collapse. In the case of Crestor (rosuvastatin), the brand sold for $320 a month. After the first generic entered, prices fell to around $90. By the time eight generics were on the market, the same pill cost just $10. That’s an 97% drop in less than two years. And this isn’t rare. It’s the standard pattern.

Why the Second and Third Generics Hit Hardest

The biggest price plunge doesn’t happen between the brand and the first generic. It happens between the second and third competitors. The FDA found that with one generic, prices sit at 83% of the brand’s cost. Add a second, and it drops to 66%. Bring in a third? It crashes to 49%. That 17-point drop in just one step is where most of the savings for patients and insurers come from.

Why? Because competition turns from a solo race into a free-for-all. The first generic had no rivals. The second one had to undercut it. The third had to undercut both. By the time you hit five or more manufacturers, prices stabilize around 17% of the original brand price. That’s the new normal.

But here’s the catch: not all generics are created equal. Some are simple pills-like metformin or lisinopril-where anyone with a decent lab can make them. Others, like complex injectables or inhalers, require advanced technology. For those, only a few companies can compete, so prices don’t fall as hard. Oncology generics, for example, often stay at 35-40% of brand price even with multiple competitors, because manufacturing them is harder and riskier.

Authorized Generics: The Brand’s Secret Weapon

Here’s where things get tricky. Sometimes, the brand company doesn’t just sit back and wait. They launch their own generic-called an authorized generic-on the same day the first generic hits the shelves. It’s the same drug, same factory, same packaging. Just sold under a different label.

This isn’t illegal. It’s legal under the Hatch-Waxman Act. And it’s devastating for the first generic. In the Januvia (sitagliptin) market, Merck launched its authorized generic the exact day the first competitor entered. Within six months, Merck’s version had captured 32% of the market. The first generic’s share dropped from 75% to 45%. Revenue? Down 35%.

According to FDA data, 65% of high-value brand drugs do this. It’s not a mistake-it’s strategy. The brand keeps revenue flowing while technically allowing competition. And because the authorized generic is identical, pharmacies and insurers often prefer it. No one wants to switch between two slightly different versions of the same pill.

Who Gets to Enter Next? It’s Not Just About Approval

You might think once the FDA approves a generic, it’s game on. But that’s only half the battle. The real fight happens in the back rooms of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and group purchasing organizations (GPOs).

Most hospitals and insurers don’t buy drugs based on FDA approval. They buy based on contracts. And increasingly, those contracts are winner-take-all. The first generic to sign a deal with a major PBM gets 100% of the business. Even if three other generics are approved and cheaper, they’re locked out.

That’s why timing matters more than ever. The second generic might get FDA approval before the third, but if the third signs a PBM contract first, it wins the market. It’s like a race where the finish line moves.

And getting that contract takes time. On average, it takes a subsequent generic 9-12 months to get on formulary lists. During that time, they’re selling to only 5-10% of the market-even though they’re approved and ready to ship.

Manufacturing: The Hidden Bottleneck

Here’s another twist: most second- and third-wave generics aren’t made by the companies that sell them. They’re made by contract manufacturers-CMOs. While the first generic might own its own plant, later entrants rent space. Why? Because building a facility costs tens of millions. Renting is cheaper, faster, and less risky.

But that creates a problem. When multiple companies rely on the same CMO, a single quality issue can shut down supply for everyone. The FDA reported that 62% of generic drug shortages involve products with three or more manufacturers. It’s not that there’s too little demand-it’s that too many are depending on too few factories.

And when one plant fails, prices spike again. For a brief moment, the market goes back to scarcity. That’s why some manufacturers now spread production across multiple CMOs-even if it raises costs. It’s insurance against collapse.

Patent Games and Legal Delays

Brand companies don’t just sit back and watch. They fight back. Between 2018 and 2022, they filed over 1,200 citizen petitions with the FDA-mostly targeting drugs that already had one generic approved. Each petition delays the next entrant by an average of 8.3 months.

These petitions often claim safety issues, manufacturing flaws, or bioequivalence concerns. Sometimes they’re legitimate. Often, they’re not. But they work. They tie up FDA resources. They scare off smaller companies with limited budgets.

Meanwhile, patent settlements have become more strategic. In 2022, 65% of patent deals included staggered entry dates. Take Humira’s biosimilars: six companies agreed to enter the market between 2023 and 2025, not all at once. That keeps prices from crashing too fast-and keeps revenue flowing for the brand longer.

The New Players: Innovation vs. Efficiency

The generic industry is splitting into two camps. One group focuses on innovation: complex generics, specialty formulations, drugs that are hard to copy. These companies charge more, compete on quality, and face fewer rivals.

The other group is all about efficiency: making the cheapest version of a common pill, competing on price, and hoping to survive the bloodbath. These companies operate on razor-thin margins. One bad batch, one lost contract, and they’re out.

That’s why the number of active generic manufacturers has dropped. In 2018, there were 142 companies holding ANDA approvals. By 2022, it was down to 97. Many exited because they couldn’t survive the price wars. Others were bought out. The market is becoming more concentrated, not more competitive.

Biosimilars: A Different Game

Biosimilars-generic versions of biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel-are not the same as traditional generics. They’re more complex. They cost $100-250 million to develop. They take years to get approved. And even with four competitors, prices only drop to 50-55% of the brand price.

That’s because you can’t just reverse-engineer a biologic like you can a pill. The manufacturing process is a black box. Even tiny changes can affect safety. So competition is slower, and prices stay higher longer.

But that’s changing. By 2027, experts predict 70% of simple generics will have five or more competitors. For biosimilars? Expect two to three players per drug. The market won’t be saturated. It’ll be controlled.

What Happens When Too Many Companies Enter

There’s a paradox here: more competition should mean lower prices and better access. And it does-for a while. But then the system breaks.

When prices fall too fast, manufacturers can’t make money. They cut corners. They stop investing. They exit the market. And then-boom-shortages. In 2022, 37% of generic markets with multiple competitors had shortages within 18 months. That’s nearly five times higher than during the first generic’s exclusivity period.

It’s not that people need less medicine. It’s that the system rewards speed over sustainability. Companies rush in, slash prices, and then vanish when profits disappear. The result? Patients wait longer for essential drugs. Pharmacists scramble to find replacements. Hospitals ration.

Some experts, like Dr. Aaron Kesselheim at Harvard, say the system has perverse incentives: too many companies chase too few simple drugs, leading to unsustainable competition. Others, like former FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb, argue for market-based fixes: restricted entry, long-term contracts, or even limited-price floors to keep manufacturers in the game.

Right now, the market is a rollercoaster. One day, a pill costs $100. The next, $1. The next, it’s not available at all.

14 Comments

The whole generic drug system is a rigged casino where the house always wins. First generic gets a 180-day jackpot, then gets gutted by authorized generics and PBM contracts. Meanwhile, the brand company laughs all the way to the bank with their identical copycat pill. This isn't competition-it's corporate theater.

One must observe, with a certain degree of intellectual consternation, the grotesque commodification of human health under neoliberal pharmaceutical capitalism. The very notion that a life-saving medication-once a product of scientific ingenuity-is now reduced to a race-to-the-bottom pricing war, speaks volumes about the moral decay of our institutions.

The FDA is totally in the pocket of Big Pharma they just approve stuff and pretend its fair but everyone knows the real players are the PBMs and the CMOs nobody talks about this because its too messy

I’ve seen this play out in my hospital’s pharmacy. One month, metformin is $3 a pill. Next month, it’s $0.15. The month after that? Out of stock. It’s not a market-it’s a cycle of panic and collapse. We need stability, not chaos.

Did you know the same companies that make generics also own the patent law firms that file those citizen petitions? The FDA doesn't regulate them-they're owned by the same private equity firms that bought the brand-name companies. This isn't a market failure. It's a coordinated takeover.

Man, I used to work at a small generic lab. We made lisinopril for pennies. Then the big PBM signed a deal with one company and we got dumped overnight. We had to lay off half the staff. This isn’t capitalism-it’s survival of the luckiest.

Think about it-this whole system is designed to make us dependent on a fragile, profit-driven machine. We’ve turned medicine into a commodity, and now we’re surprised when it breaks? The real tragedy isn’t the price drop-it’s that we stopped asking why we let this happen in the first place.

Authorized generics are not a loophole. They are a contractual provision explicitly permitted under the Hatch-Waxman Act. To call them deceptive is factually incorrect. The drug is identical. The labeling is different. That is not fraud. That is commerce.

You Americans think this is bad? In Nigeria, we don't even have generics. We get expired brand drugs from Europe labeled as "new." You complain about $1 pills? We're happy when we get $10 pills that aren't fake. Your system is broken but at least you have a system.

The erosion of trust in pharmaceutical supply chains is not merely economic-it is existential. When a patient cannot rely on consistent access to essential medication, the social contract fractures.

Let’s be real: if you can’t compete on price, you shouldn’t be in the game. The market sorts out the weak. End of story.

My cousin in India makes generic insulin. He doesn’t have fancy labs-he has a small plant and a lot of grit. He told me: "We don’t compete with the big boys. We compete with death." That’s the real story behind the $1 pill.

Did you know that the same Chinese factories that make your generic metformin also make the active ingredients for antidepressants, antibiotics, and heart meds? And those factories are run by state-owned companies that answer to Beijing? So every time your prescription price drops, you’re not just saving money-you’re funding a geopolitical strategy. Nobody talks about this because it’s too scary. But it’s true. The entire global generic supply chain is a single, vulnerable node-and it’s in China. And they control it.

It’s funny how we call it "competition" when it’s really just a race to the bottom. We praise efficiency but punish sustainability. We want cheap drugs but don’t want to pay for the people who make them. Maybe the real question isn’t how to fix the market-but whether we want a market at all.

Write a comment