When a scan for something else - like a back pain or abdominal discomfort - turns up an unexpected lump on the adrenal gland, it’s called an adrenal incidentaloma. It sounds scary, but here’s the truth: about 80% of these are harmless, non-functioning tumors that never cause symptoms and don’t need treatment. The real challenge isn’t finding them - it’s figuring out which ones might be dangerous.

What Exactly Is an Adrenal Incidentaloma?

An adrenal incidentaloma is a mass larger than 1 centimeter found by accident during imaging done for another reason. These aren’t symptoms-driven discoveries. You don’t feel it. You don’t know it’s there. It shows up on a CT or MRI ordered for gallstones, kidney stones, or even a car accident. The prevalence jumps with age - 2% in people under 50, but over 7% in those over 70. That’s because older adults get more scans. More scans mean more incidental findings. The adrenal glands sit on top of each kidney. They make hormones that control blood pressure, metabolism, stress response, and electrolyte balance. When a tumor forms there, it can either sit quietly - or start pumping out too much of one of these hormones. That’s where the risk lies.Three Types of Adrenal Masses - And What They Mean

Not all adrenal tumors are the same. They fall into three clear groups:- Functioning tumors - These make extra hormones. Examples include pheochromocytomas (adrenaline), cortisol-producing tumors (Cushing’s syndrome), and aldosterone-secreting tumors (high blood pressure, low potassium).

- Malignant tumors - These are cancerous. Either primary adrenocortical carcinoma (rare, about 2% of incidentalomas) or cancer that spread from elsewhere (like lung or breast cancer).

- Non-functioning benign tumors - The most common type. These are usually adenomas, myelolipomas, or cysts. They don’t make hormones and don’t grow fast. They’re just there.

Step 1: Rule Out Pheochromocytoma First

Before anything else - even before looking at the scan - you must check for pheochromocytoma. Why? Because if you miss it and operate, you could trigger a deadly surge of adrenaline during surgery. Blood pressure can spike to stroke-levels. Death can happen. The test? Plasma-free metanephrines or 24-hour urinary fractionated metanephrines. These measure breakdown products of adrenaline and noradrenaline. If they’re high, you don’t go to surgery until you’ve treated the tumor with alpha-blockers for at least 7-14 days. This isn’t optional. It’s life-saving. Even if you have no symptoms - no headaches, no sweating, no racing heart - you still get tested. About 4% of incidentalomas are pheochromocytomas, and many are silent.Step 2: Check for Cortisol Overproduction

Next, test for autonomous cortisol secretion - also called subclinical Cushing’s syndrome. This affects 5-10% of incidentalomas. It doesn’t always look like classic Cushing’s (moon face, buffalo hump). Instead, it might just mean high blood pressure, diabetes, or osteoporosis that won’t improve. The test: a 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test. You take a pill at night. The next morning, you get a blood draw. If your cortisol level is above 1.8 μg/dL (50 nmol/L), it’s suspicious. Above 5.0 μg/dL? That’s a strong signal for surgery, especially if you have metabolic issues. Newer tests like urinary steroid metabolomics are showing promise - they’re 92% accurate at spotting cortisol excess, better than the dexamethasone test. But they’re not widely available yet.Step 3: Screen for Aldosterone - Only If You Have High Blood Pressure

If you have high blood pressure, especially if it’s hard to control or you have low potassium, check for primary hyperaldosteronism. This happens in about 4% of incidentalomas. Test: plasma aldosterone concentration and plasma renin activity. The aldosterone-to-renin ratio tells you if your adrenal is making too much aldosterone. If yes, surgery may be better than lifelong pills.

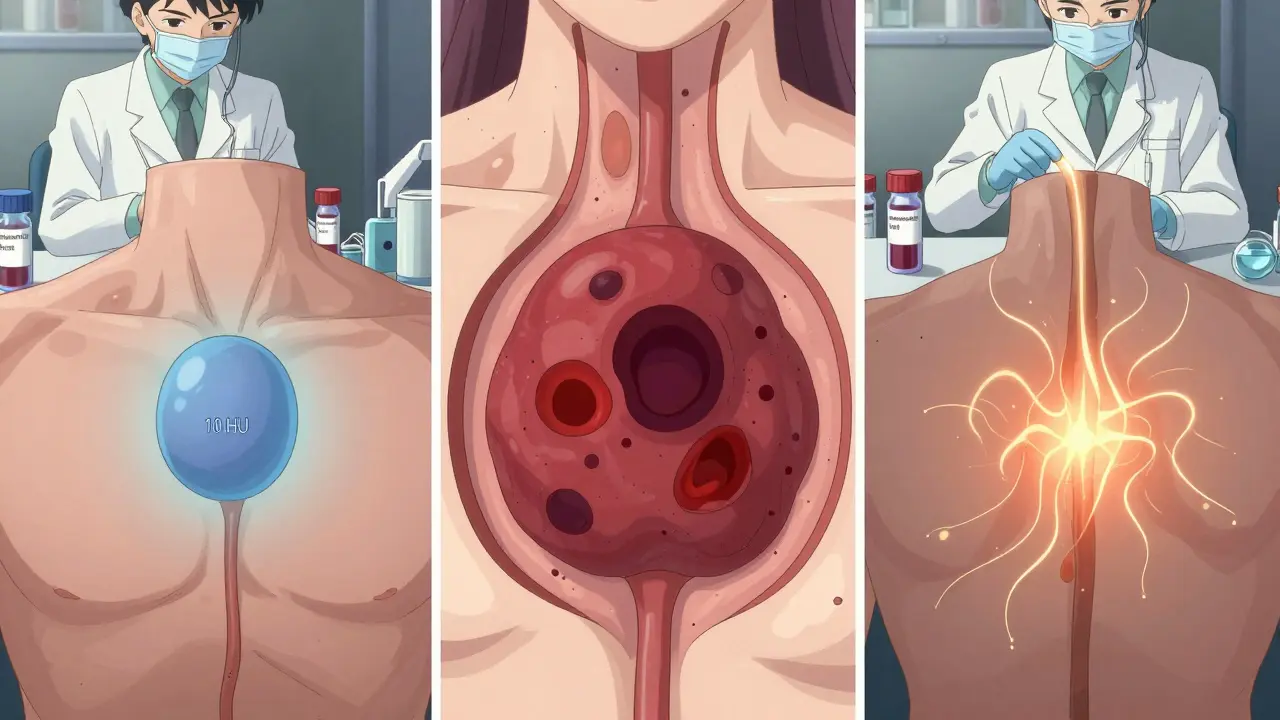

Step 4: Read the Scan - Size and Shape Matter

A non-contrast CT scan is the first imaging test. It’s cheap, fast, and tells you a lot. The key number? Hounsfield units (HU). If the tumor has a density below 10 HU, it’s almost certainly a benign adenoma - 70-80% accurate. Fat inside the tumor (seen as dark spots) also points to benign. Myelolipomas have fat. Hematomas have blood. If the tumor is:- Over 4 cm - higher chance of cancer

- Over 6 cm - 25% risk of adrenocortical carcinoma

- Irregular edges, uneven texture, or rapid growth - red flags

When Is Surgery Necessary?

You need surgery if:- The tumor is producing hormones (pheochromocytoma, cortisol excess, aldosterone excess)

- The tumor is over 4 cm

- The tumor has imaging features suggesting cancer (irregular shape, high density, necrosis)

- The tumor grows fast - more than 1 cm per year

What About Small, Benign, Non-Functioning Tumors?

If your tumor is under 4 cm, has low Hounsfield units, no hormone excess, and no growth - you’re done. No follow-up scans. No blood tests. No stress. Some doctors still order yearly scans out of habit. But the guidelines are clear: if it’s clearly benign and not making hormones, no monitoring is needed. You save money, radiation exposure, and anxiety.Why This Matters - The Human Side

Patients often feel terrified after hearing "tumor." Even if it’s benign, the wait for test results causes real stress. One informal survey of 142 patients found 78% felt high anxiety during evaluation. The best outcomes come from specialized centers. At places like Columbia’s Adrenal Center, 92% of patients report satisfaction. At general hospitals? Only 68%. Why? Because adrenal work needs a team: endocrinologist, radiologist, surgeon - all experienced. Most community hospitals don’t have access to plasma metanephrine testing. Only 45% do. And radiologists without adrenal expertise misread scans 15-30% of the time.

The Future: More Precision, Less Guesswork

New tools are coming. Urinary steroid metabolomics is one. It looks at dozens of cortisol breakdown products at once - far more accurate than one blood test. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s the future. The Endocrine Society is updating its guidelines in 2024 to reflect new data: surgery for subclinical Cushing’s improves blood sugar, blood pressure, and bone density - especially when cortisol levels are above 5.0 μg/dL. The big picture? We’re moving from "one-size-fits-all" to personalized risk. A 72-year-old with a 3.5 cm tumor, normal hormones, and diabetes might benefit from surgery. A 50-year-old with the same tumor and no health issues? Probably not.What to Do If You’re Diagnosed

If you’ve been told you have an adrenal incidentaloma:- Don’t panic. Most are harmless.

- Ask for plasma-free metanephrines and 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test.

- Get the non-contrast CT scan reviewed by someone who reads adrenal images regularly.

- If hormone levels are high or the tumor is over 4 cm, ask for a referral to an adrenal specialist.

- If everything looks normal - ask if you need any follow-up. The answer might be no.

Common Misconceptions

- "All adrenal tumors need surgery." False. Most don’t.

- "If I have high blood pressure, it’s from the tumor." Maybe. But not always. Test before assuming.

- "I need a yearly scan." Only if the tumor is indeterminate. Otherwise, no.

- "I’ll feel symptoms if it’s dangerous." Pheochromocytomas and cortisol excess can be silent. That’s why testing is mandatory.

Final Thoughts

Adrenal incidentalomas are a product of modern medicine - we see more because we scan more. But seeing more doesn’t mean treating more. The art is knowing when to act - and when to do nothing. The guidelines are clear. The science is solid. The biggest barrier isn’t medical - it’s awareness. Too many patients get lost in the system, getting unnecessary tests and surgeries because no one connected the dots. If you’ve been diagnosed, be your own advocate. Ask for the right tests. Ask for a specialist. And remember - not every lump needs to be removed. Sometimes, the best treatment is no treatment at all.Are all adrenal incidentalomas cancerous?

No. About 80% of adrenal incidentalomas are benign, non-functioning adenomas that don’t cause symptoms or need treatment. Only 2-8% are malignant, and most of those are either primary adrenocortical carcinoma or metastatic cancer from another organ.

Do I need surgery if I have an adrenal tumor?

Not necessarily. Surgery is recommended only if the tumor is over 4 cm, shows signs of cancer on imaging, produces excess hormones (like cortisol, adrenaline, or aldosterone), or grows rapidly (more than 1 cm per year). Most small, non-functioning tumors require no treatment.

What tests are needed to evaluate an adrenal incidentaloma?

Three key tests are required: 1) Plasma-free metanephrines or 24-hour urinary metanephrines to rule out pheochromocytoma; 2) A 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test to check for cortisol overproduction; and 3) Plasma aldosterone and renin levels if you have high blood pressure or low potassium. A non-contrast CT scan is also used to assess size and density.

Can an adrenal tumor cause high blood pressure?

Yes. Tumors that produce aldosterone (primary hyperaldosteronism) or adrenaline (pheochromocytoma) can cause severe or hard-to-control high blood pressure. Cortisol-producing tumors can also raise blood pressure through metabolic effects. Testing for these hormones is essential in anyone with hypertension and an adrenal mass.

How often should I get follow-up scans if my tumor is benign?

If your tumor is under 4 cm, has low density on CT (under 10 HU), and shows no hormone excess, no follow-up scans or blood tests are needed. Guidelines from the Endocrine Society state that routine monitoring is unnecessary for clearly benign, non-functioning tumors. Only indeterminate cases need imaging every 6-12 months.

Why is pheochromocytoma so dangerous if missed?

If a pheochromocytoma is undiagnosed and surgery is performed, the stress of anesthesia can trigger a massive release of adrenaline, causing a sudden, life-threatening spike in blood pressure. This can lead to stroke, heart attack, or death. That’s why testing for metanephrines is mandatory before any adrenal surgery.

Is adrenal cancer common in incidentalomas?

Rare. Only about 2% of adrenal incidentalomas are adrenocortical carcinoma. The risk increases with size - tumors larger than 6 cm have a 25% chance of being cancerous, while those under 4 cm have less than a 1% risk. Size, shape, and growth rate matter more than the tumor being "found by accident."

What’s the difference between subclinical and full Cushing’s syndrome?

Full Cushing’s syndrome has clear signs: weight gain, purple stretch marks, muscle weakness, easy bruising. Subclinical Cushing’s means cortisol is slightly elevated - you may have high blood pressure, diabetes, or osteoporosis, but no obvious physical signs. Even so, it increases heart disease and death risk. Surgery can reverse these problems.

12 Comments

So let me get this straight - we’re doing all these tests because we found a lump? In 2024? We used to just watch and wait. Now it’s scan, blood draw, repeat, referral, another scan, and then maybe surgery? All for something that’s probably nothing. This is medicine turned into a money machine.

Man, I hate how we overmedicalize everything. Back in my day, if you didn’t feel sick, you didn’t get cut open. Now they’re scanning grandma for back pain and suddenly she’s on a surgical prep list. We’re turning healthy people into patients just to justify the CT machine’s rent.

This is actually really helpful. I was terrified after my scan came back with a 3.2 cm nodule - I thought I had cancer. Reading this made me breathe again. Thank you for explaining the 80% stat so clearly. Sometimes doctors just say "it’s probably fine" and leave you hanging. You actually gave me the tools to ask the right questions.

They don’t want you to know this - but adrenal tumors are often caused by EMF radiation from 5G towers and fluoride in the water. The pharmaceutical industry pushes all these tests because they profit from surgery and lifelong meds. The real solution? Detox with bentonite clay and sunlight. No scans needed.

Not every lump needs removal. The real art is knowing when not to act.

Who’s really behind this? The WHO? The AMA? Big Pharma? They want us scared. They want us scanning. They want us on meds. They don’t care if you live or die - they care if your insurance pays. They’re using adrenal tumors to normalize surveillance. Wake up.

Okay but what if the radiologist is just bad? I saw a post where someone’s tumor was labeled "benign" and turned out to be cancer. What if the Hounsfield units are wrong? What if the test was done wrong? I’m just saying… what if none of this is reliable? 😬

Thank you for writing this - I’ve been so anxious since my diagnosis and this actually calmed me down 🙏 I’m going to print it out and take it to my doctor tomorrow. Also, I didn’t know about the urinary steroid thing - that sounds amazing! Do you think it’ll be available in small towns soon? 🤞

This is an excellent, well-structured overview. I work in primary care and see patients terrified by incidental findings every week. Your breakdown of the three categories and clear guidelines for action versus observation is exactly what’s missing from most patient handouts. I will be sharing this with my team and my patients. Thank you for the clarity and compassion.

Let’s be real - this isn’t medicine, it’s epistemological theater. We’re measuring Hounsfield units like they’re sacred glyphs while ignoring the ontological void of medicalization itself. The tumor is not the problem - the gaze is. The scan is a fetish object. The hormone panel, a ritual sacrifice to the altar of diagnostic certainty. We’ve replaced wisdom with algorithmic anxiety. The body is not a machine to be calibrated - it’s a mystery to be endured. And yet, we dissect it with the fervor of priests at a quantum altar. What are we afraid of? Not the tumor. We’re afraid of not knowing. And so we scan. And scan. And scan. Until the silence between the pixels screams louder than the mass itself.

This is so important - thank you for writing it so clearly! I’ve seen so many patients get lost in the system, especially older folks who just want to be told, "You’re okay." I love how you emphasize that no follow-up is needed for clearly benign cases. So many of my patients come in with stacks of scans from different clinics - all because someone said, "Just to be safe." We need to stop doing "just to be safe" medicine. It’s exhausting, expensive, and emotionally devastating. Let’s protect people from unnecessary fear - not just from tumors.

You’re right to say not every tumor needs surgery - but you’re also ignoring the fact that guidelines are written by committees who’ve never held a scalpel. Real surgeons know: if it’s over 3 cm, and it’s not clearly fat, you remove it. You don’t wait for it to grow. You don’t gamble with cancer. The data says 2% are malignant - but 2% is 100% for the person who gets it. Play it safe. Cut it out.

Write a comment