Amblyopia, often called "lazy eye," isn’t just a weak eye-it’s a brain problem. When a child’s visual system doesn’t develop properly because one eye isn’t sending clear signals to the brain, the brain starts ignoring that eye. Over time, this leads to permanent vision loss in the affected eye-if left untreated. It’s the most common cause of vision problems in kids, affecting 2% to 4% of children worldwide. The good news? With the right treatment at the right time, most kids can regain normal or near-normal vision.

How Amblyopia Develops

Amblyopia doesn’t happen overnight. It forms during the first few years of life, when the brain is learning how to see. This window, called the critical period, lasts from birth until about age 7. During this time, the brain builds connections between the eyes and the visual cortex. If something blocks or blurs vision in one eye-even briefly-the brain starts to favor the clearer image from the other eye. The weaker eye gets sidelined, and its connection to the brain fades. There are three main types of amblyopia, each with a different cause:- Strabismic amblyopia (about 50% of cases): One eye turns inward, outward, up, or down. The brain ignores the misaligned eye to avoid double vision.

- Anisometropic amblyopia (about 30%): The two eyes have very different prescriptions. One eye sees clearly; the other sees blurry. The brain relies on the clear image and ignores the blurry one.

- Deprivation amblyopia (10-15%): Something physically blocks light from entering the eye-like a cataract, droopy eyelid (ptosis), or clouded cornea. This is the most serious type and needs urgent treatment.

Even kids with no obvious eye problems can develop amblyopia. Premature babies, those with low birth weight, or kids with a family history of lazy eye are at higher risk. That’s why routine eye exams starting at age 1 are so important.

Why Early Detection Matters

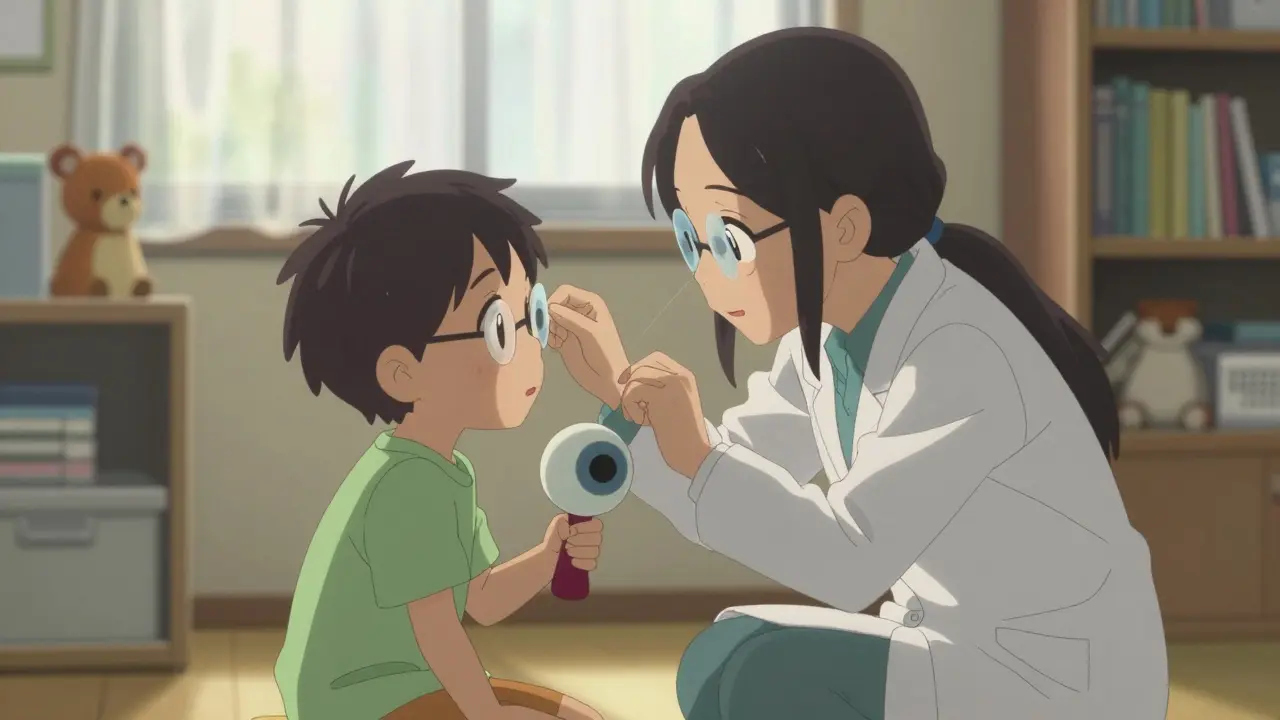

Many parents assume their child sees fine because they don’t complain or bump into things. But amblyopia often goes unnoticed. Kids don’t know what normal vision feels like. If one eye is weak, they just use the good one and adapt. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vision screening at 1, 2, and 3 years old. Pediatricians use simple tools like photoscreeners or cover tests to catch problems early. A full eye exam by a pediatric ophthalmologist is needed if anything looks off. The earlier treatment starts, the better the outcome. Children treated before age 5 have an 85-90% chance of recovering normal vision. Between ages 5 and 7, that drops to 50-60%. After age 8, improvement becomes much harder-and rare. That’s why waiting is dangerous.Patching Therapy: The Gold Standard

Patching is the most proven treatment for amblyopia. It works by forcing the brain to use the weaker eye. A patch is placed over the stronger eye for several hours a day, making the lazy eye work harder. Over time, the brain rewires itself to pay attention to the signals from that eye. The old rule was: patch for 6 hours a day. But research changed that. The landmark Amblyopia Treatment Study (ATS), which followed over 500 children between 2002 and 2011, found that for moderate amblyopia (vision between 20/40 and 20/100), just 2 hours of daily patching worked just as well as 6 hours. That’s a huge relief for families. For severe cases (vision worse than 20/100), doctors often start with 6 hours and adjust based on progress. The goal isn’t just better vision-it’s restoring depth perception and binocular vision so both eyes work together.

What If My Child Won’t Wear the Patch?

This is the biggest hurdle. Most kids hate wearing patches. They feel different. Their skin gets irritated. Other kids tease them. Studies show only 40-60% of kids stick with patching as prescribed. Successful families don’t just slap on a patch and hope for the best. They build routines:- Start small: 30 minutes a day, then slowly increase.

- Use fun activities: Coloring, puzzles, tablet games-all done while patched.

- Make it a reward: A sticker chart, small prizes, or a "patching party" with a sibling or friend.

- Use digital tools: Apps like "LazyEye Tracker" help log hours and send reminders. Over 20% of pediatric eye clinics now use them.

Some parents try "atropine drops" instead. One drop in the stronger eye every day blurs its near vision, making the child use the weaker eye for reading and close work. Studies show it works just as well as patching for moderate cases, and compliance is higher because there’s no visible patch.

Other Treatments Beyond Patching

Patching isn’t the only option. Depending on the cause, other treatments may be needed:- Atropine drops: As mentioned, these blur the good eye. They’re especially useful for kids who refuse patches or have mild-to-moderate amblyopia.

- Bangerter filters: These are translucent stickers placed on glasses lenses to blur the strong eye. Less noticeable than patches, they work best for older kids.

- Vision therapy: Exercises to improve eye tracking, focusing, and coordination. When added to patching, studies show 15-20% better results in depth perception.

- Surgery: For kids with strabismus or cataracts, correcting the physical problem comes first. But surgery alone doesn’t fix amblyopia-patching still follows.

There’s also new tech on the horizon. Digital games like AmblyoPlay, cleared by the FDA in 2021, turn vision therapy into fun apps. Kids play for 15-30 minutes a day, and the game adjusts difficulty based on their performance. In European clinics, compliance jumps to 75%-far higher than patching.

Even more exciting: early trials of transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS)-a mild electrical current applied to the scalp-showed 40% better vision gains when paired with patching. It’s still experimental, but it points to a future where brain stimulation helps rewire vision faster.

How Long Does Treatment Take?

This isn’t a quick fix. Most kids need at least 6 months of treatment. Some need up to 2 years. Progress isn’t always linear. Vision might improve fast at first, then stall. That’s normal. Regular checkups every 4-8 weeks are crucial. The doctor checks visual acuity, eye alignment, and how well the child is using both eyes together. If progress stalls, the treatment plan changes-maybe more patching, switching to atropine, or adding vision therapy.Can Adults Be Treated?

For decades, doctors believed amblyopia couldn’t be fixed after childhood. That’s not entirely true anymore. Recent studies show adults with lazy eye can improve vision with intensive perceptual learning-like playing visual discrimination games for hours a day, several times a week. But results are modest. Adults rarely reach 20/20 vision. The brain’s plasticity is much lower after age 10. That’s why early childhood remains the golden window. The goal isn’t to give adults false hope-it’s to remind parents: if your child has a vision problem, don’t wait.What Parents Need to Know

- Screen early: Get your child’s eyes checked by age 1, again at age 3, and before kindergarten. - Don’t ignore squinting or head tilting: These can be signs of an eye turn or blurry vision. - Follow through: Even if your child cries or refuses, consistency beats perfection. Two hours a day, five days a week, is better than six hours once a week. - Ask about alternatives: If patching isn’t working, talk to your doctor about atropine or digital therapy. - Celebrate small wins: Every improvement counts-even if it’s just one line better on the chart.Over 97% of children with amblyopia will see some improvement with treatment. But only 65-75% will reach full 20/20 vision. The rest still gain functional vision-enough to drive, read, and live independently. That’s the power of early action.

Amblyopia isn’t just about seeing clearly. It’s about giving a child the chance to see the world in full depth, with both eyes working as a team. That’s why patching isn’t just a treatment-it’s a gift of sight.

8 Comments

So let me get this straight-we’re telling parents to strap a patch on their kid’s face for hours a day, and the only reason it works is because the brain is still malleable? Meanwhile, adults who’ve lived with this their whole life are told to just ‘accept it’? That’s not medicine, that’s biological ageism wrapped in a sticker chart.

And don’t get me started on the ‘fun games’ replacing patches. If your child’s vision is failing, you don’t turn it into a TikTok challenge. You fix it. No rewards. No parties. Just discipline.

Also, 20% of clinics use tracking apps? That’s not innovation-that’s just admitting 80% of doctors still hand out paper logs like it’s 1998.

From a neuro-ophthalmological standpoint, the critical period hypothesis remains robust, but recent fMRI studies (e.g., Hess et al., 2020) suggest that binocular rivalry suppression mechanisms in V1 and V2 may be more dynamically modifiable than previously assumed-even in post-pubertal subjects.

Moreover, the efficacy of atropine penalization is contingent upon the anisometropic gradient; when the interocular refractive difference exceeds 1.50 D, compliance and outcomes correlate more strongly than with patching alone, per the ATS-5 protocol.

That said, the psychosocial burden of occlusion therapy is non-trivial, and digital therapeutics like AmblyoPlay represent a paradigm shift in adherence metrics-not because they’re ‘fun,’ but because they leverage operant conditioning via variable-ratio reinforcement schedules.

And yes, tRNS is still Phase II, but the effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.78) in the 2023 Munich trial is statistically significant and clinically meaningful. We’re on the cusp of neuromodulatory adjuncts becoming standard of care.

My cousin’s kid had this. Patching was a nightmare-she’d rip it off in the car, scream at school, the whole thing. We switched to atropine drops and it was night and day. No one even noticed she was doing treatment. She’s 10 now, sees fine, plays soccer. No drama.

Just saying-there’s more than one way to skin this cat. Don’t let guilt make you stick to the ‘gold standard’ if it’s breaking your family apart.

It is imperative to underscore that amblyopia, as a neurodevelopmental disorder of the visual cortex, constitutes a public health priority, particularly within pediatric populations exhibiting elevated risk factors such as prematurity, low birth weight, and familial predisposition.

While occlusion therapy remains the cornerstone of intervention, the increasing prevalence of digital alternatives necessitates rigorous longitudinal validation prior to widespread clinical adoption.

Furthermore, the assertion that ‘adults cannot be treated’ is an oversimplification; emerging evidence suggests that perceptual learning paradigms, when administered with high dosage and fidelity, may yield modest but functionally significant improvements in visual acuity and contrast sensitivity.

Therefore, clinicians are advised to maintain a nuanced, evidence-based approach, avoiding both therapeutic nihilism and unvalidated technological hype.

My little brother had this when he was 4. We did patching for 8 months. He hated it. But we made it a game-he got to pick the patch design every week. One week it was Spider-Man, next week it was dinosaur. He started asking for it.

Now he’s 18, plays guitar, drives, sees 20/20. No surgery, no fancy tech. Just patience and stupid stickers.

Parents: you don’t need to be perfect. Just show up. Every day.

It is deeply concerning that the medical community has, in recent years, embraced a culture of appeasement over accountability in pediatric vision care. The suggestion that ‘two hours a day, five days a week’ is sufficient, when the gold standard is clearly six hours, represents a dangerous dilution of clinical rigor.

Moreover, the normalization of digital ‘games’ as therapeutic substitutes is a capitulation to parental laziness and technological distraction. Children are not video game characters; their neural pathways are not optimized for gamified reinforcement.

And let us not forget: the 40% non-compliance rate with patching is not a failure of the treatment-it is a failure of parental discipline. If you cannot enforce a two-hour daily patching regimen for your child’s lifelong visual health, you have no business being a parent.

The fact that atropine drops are being marketed as a ‘convenient alternative’ is a travesty. Blurring the vision of a healthy eye is not treatment-it is chemical coercion.

And tRNS? A gimmick. Experimental noise masquerading as science. We are not living in a sci-fi novel. Stick to the protocol. Or stop pretending you care.

How quaint. A ‘gold standard’ that’s been in use since the 1950s. And yet, we’re still treating children like lab rats with duct tape over their eyes?

Meanwhile, in Sweden, they’ve been using binocular dichoptic training since 2017-no patches, no drops, just synchronized VR goggles that force both eyes to work together from day one.

And yet, here we are, clinging to patching like it’s a moral virtue. It’s not medicine-it’s tradition dressed in white coats.

Also, ‘sticker charts’? Really? You’re rewarding a child for not being blind? What’s next-a lollipop for breathing?

ok but what if the patch is just making the brain more confused?? like what if the brain is trying to protect the kid from trauma?? i heard on a podcast that lazy eye is linked to childhood stress and the brain shuts down the eye to avoid seeing scary stuff??

also i think the government is hiding the real cure because big pharma makes billions off patches and drops and no one wants to talk about the truth

my cousin’s neighbor’s dog had better vision than my nephew after patching... just saying

Write a comment