When you’re heading up a mountain for a pilgrimage or a long trek, your body doesn’t just face physical exhaustion-it faces a silent threat: low oxygen. At 14,000 feet, the air holds nearly 40% less oxygen than at sea level. That’s not just uncomfortable-it can be deadly if you’re unprepared. Thousands of pilgrims and trekkers every year end up in emergency situations simply because they didn’t plan for their medications in advance. This isn’t about being overly cautious. It’s about survival.

Know Your Risk Zone

Altitude sickness doesn’t wait for you to feel ready. It hits fast, especially when you fly or drive straight into high elevations-like landing in Lhasa at 12,000 feet or taking a bus to Mount Kailash. The risk starts climbing above 8,000 feet. By 14,000 feet, nearly half of all travelers show symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS): headaches, nausea, dizziness, and fatigue. At 17,500 feet-Everest Base Camp territory-those numbers jump to 43%. And if you ignore it, AMS can turn into High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) or High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), both life-threatening.The key? Don’t wait until you’re gasping on a ridge to realize you forgot your meds. You need a plan before you leave home.

Essential Medications to Pack

Here’s what you actually need in your pack-not just what sounds good. These are the drugs backed by research, used by rescue teams, and recommended by travel medicine specialists.- Acetazolamide (Diamox): The gold standard for preventing AMS. Take 125 mg twice a day, starting one day before ascent and continuing for 3 days after reaching your highest elevation. It helps your body breathe faster, which speeds up acclimatization. Side effects? Increased urination (67% of users report this) and tingling fingers. Not a dealbreaker-just something to expect.

- Dexamethasone: This steroid is your emergency tool for HACE. If someone starts acting confused, stumbling, or vomiting uncontrollably, give 8 mg right away, then 4 mg every 6 hours. It doesn’t cure it-it buys you time to descend. Keep it separate from your daily meds.

- Nifedipine (extended-release): For HAPE, the lung version of altitude sickness. Take 20 mg every 12 hours if you’re at high risk or have had HAPE before. It opens up blood vessels in the lungs, reducing pressure.

- Diarrhea meds: Around 60% of trekkers get sick from water contamination. Pack azithromycin (500 mg once daily for 3 days) or rifaximin. Avoid loperamide alone-it stops symptoms but traps bacteria. Always pair it with antibiotics.

- IBU or acetaminophen: For headaches and pain. Ibuprofen (400 mg) works better than acetaminophen for altitude-related headaches.

- Antihistamines: Diphenhydramine (25-50 mg) helps with allergic reactions or sleep issues caused by altitude-induced insomnia.

- Topicals: Antibiotic ointment, hydrocortisone cream, and blister pads. You’ll thank yourself when your boots rub raw.

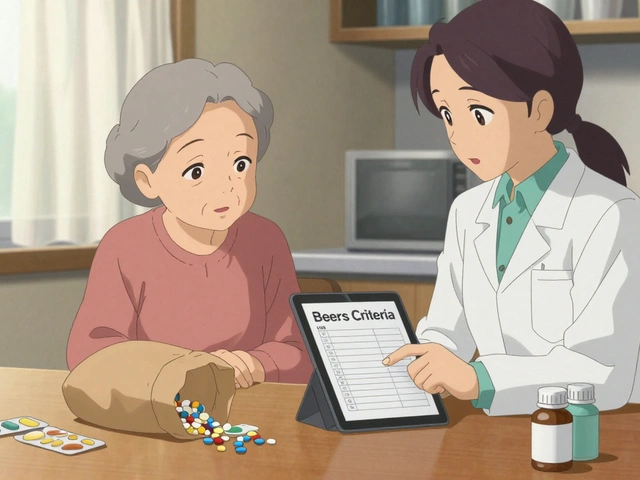

Don’t forget your regular prescriptions. If you take blood pressure pills, insulin, or thyroid meds-bring double what you think you’ll need. Cold temperatures can ruin them.

Storage Matters More Than You Think

Medications aren’t like socks. They don’t survive freezing nights or scorching midday sun. Insulin degrades by 25% in just 24 hours below 32°F. Glucometers give wrong readings at -10°C. Your asthma inhaler might not spray properly in thin air.Use insulated, waterproof cases. Keep them close to your body-inside your jacket, not in your backpack. At night, sleep with them under your pillow. If you’re diabetic, carry a small hand warmer to keep your insulin warm. Test your glucose meter at altitude before relying on it. Many trekkers don’t realize their device is giving false readings until it’s too late.

And always carry meds in their original bottles with pharmacy labels. Airport security and border agents ask for proof. If you’re carrying controlled substances-like strong painkillers or ADHD meds-get a letter from your doctor. Some countries require special permits. Don’t gamble on this. One missed form can mean a confiscated pack and a stranded trek.

Pre-Trip Medical Checkup: Don’t Skip It

You wouldn’t climb a mountain without checking your boots. Why skip your health? A 2023 study found that 83% of serious altitude illnesses could’ve been prevented with a simple pre-trip visit. Your doctor will check your heart, lungs, and blood pressure. They’ll screen for hidden conditions-like sleep apnea or heart defects-that make altitude riskier.Ask for a personalized plan. If you’re over 50, have asthma, or have had altitude sickness before, you need a different strategy. Some people can’t take acetazolamide because of sulfa allergies (3-6% of the population). Your doctor can suggest alternatives like dexamethasone or a slower ascent schedule.

And if you’re diabetic, pregnant, or on immunosuppressants? Talk to a travel medicine specialist. Not your general practitioner. Someone who knows high-altitude protocols. These doctors exist. They’re in major cities, and they’re trained for this exact scenario.

What You Can’t Rely On

Don’t count on local pharmacies. A 2013 survey found that 89% of health camps along pilgrimage routes in Nepal didn’t have acetazolamide, dexamethasone, or nifedipine. You think you’ll just buy more when you get there? You won’t. Even in towns like Lukla or Kathmandu, supplies are unpredictable. And if you’re on a remote trail? Forget it.Same goes for oxygen canisters sold to tourists. Most are underfilled, expired, or fake. Real oxygen therapy requires a regulated system-like a portable concentrator or a pressurized tank. If you need supplemental oxygen, bring your own. And know how to use it before you go.

Acclimatization: No Shortcuts

Medications help-but they don’t replace slow ascent. The Wilderness Medical Society says the safest way up is no more than 1,000 feet (305 meters) per day above 10,000 feet. That means a 14-day itinerary for Everest Base Camp. But pilgrims often can’t do that. They fly in. They rush. So here’s your backup:- Take acetazolamide before you even leave home.

- Drink 4-5 liters of water daily. Dehydration makes altitude sickness worse.

- Avoid alcohol and sleeping pills. They slow your breathing at night-exactly when you need to be alert.

- If you feel sick, don’t go higher. Rest. Wait. Descend if symptoms get worse.

There’s no magic pill that lets you skip acclimatization. If you try, you’re gambling with your life.

Emergency Backup: The Gammow Bag

If you’re leading a group or trekking in remote areas, consider a portable hyperbaric chamber-commonly called a Gammow Bag. It simulates lower altitude by pressurizing the air around you. It’s not a cure, but it can save a life while you wait for evacuation. Less than 5% of health camps carry one. If you’re going to a place without reliable rescue, bring one. Or know where to rent one.Also, carry a satellite communicator. Not just a phone. Phones don’t work at 16,000 feet. A Garmin inReach or Zoleo lets you send SOS signals. One Reddit user lost $4,200 because his insulin failed and he couldn’t call for help. He didn’t have a satellite device.

Real Stories, Real Consequences

A man from Ohio made it to 17,000 feet on his first high-altitude trek. He didn’t bring acetazolamide. He thought he’d be fine. He got HACE. His guide had to carry him down for 18 hours. He survived-but lost two toes to frostbite. A woman from India carried her insulin in a regular cooler. At 14,000 feet, it froze. Her blood sugar spiked. She collapsed. She was airlifted. Her insurance didn’t cover it because she hadn’t disclosed her diabetes during booking. A group of pilgrims from Nepal ran out of dexamethasone. They had to wait three days for a supply drop. One person died. These aren’t rare. They happen every season. And they’re preventable.Final Checklist Before You Go

- ✅ Visit a travel medicine specialist 4-6 weeks before departure

- ✅ Get prescriptions for all medications, including acetazolamide, dexamethasone, nifedipine

- ✅ Pack double the amount of all meds

- ✅ Store meds in insulated, waterproof cases-keep them warm

- ✅ Carry original pharmacy labels and doctor’s letters for controlled substances

- ✅ Bring a satellite communicator and know how to use it

- ✅ Test your glucometer at altitude before relying on it

- ✅ Know the signs of AMS, HAPE, and HACE-and what to do if they appear

- ✅ Never ascend if you’re symptomatic

This isn’t about being paranoid. It’s about being responsible. You’re not just carrying pills-you’re carrying your ability to come home.

Can I buy altitude sickness meds at local pharmacies during my trek?

No, you shouldn’t rely on it. A 2013 study found that 89% of health camps along major pilgrimage routes in Nepal didn’t stock acetazolamide, dexamethasone, or nifedipine. Even in towns like Lukla or Kathmandu, supplies are inconsistent. If you need medication, bring it from home-enough for the entire trip, plus extra.

Is acetazolamide safe for everyone?

No. People with a sulfa allergy (3-6% of the population) should avoid it. Symptoms include rash, swelling, or trouble breathing. If you’re unsure, ask your doctor for a skin test. Alternatives include dexamethasone or a slower ascent plan. Never self-prescribe if you’ve had a reaction to antibiotics like Bactrim before.

How do I store insulin at high altitude?

Keep insulin between 59-77°F (15-25°C). Below freezing, it loses potency by 25% in 24 hours. Use an insulated case with a hand warmer or keep it inside your jacket. Never leave it in your backpack overnight. Test your blood sugar frequently-glucometers can give false readings below 32°F.

Do I need a doctor’s letter for my medications?

Yes-if you’re carrying controlled substances like opioids, stimulants, or strong sedatives. Some countries require proof that the meds are prescribed to you. Even if you’re not crossing borders, airport security or trekking agencies may ask. A simple letter from your doctor stating your name, medication, dosage, and purpose is enough. Keep a copy in your bag and another in your email.

What’s the best way to prevent altitude sickness?

Slow ascent is the most effective method. Ascend no more than 1,000 feet per day above 10,000 feet. Combine that with acetazolamide, hydration (4-5 liters of water daily), and avoiding alcohol or sleep aids. If you feel symptoms, stop ascending. Rest. Descend if they worsen. Medication helps-but it doesn’t replace acclimatization.

Are oxygen canisters sold to tourists reliable?

Most are not. Many are underfilled, expired, or fake. Real oxygen therapy requires a regulated system-like a portable concentrator or pressurized tank. If you need supplemental oxygen, bring your own equipment and know how to use it. Don’t trust roadside vendors. Your life depends on it.

What should I do if someone in my group shows signs of HACE or HAPE?

Immediate descent is the only cure. Give dexamethasone (8 mg) right away for HACE, or nifedipine (20 mg) for HAPE. Use a Gammow Bag if available. Call for evacuation via satellite communicator. Do not wait. These conditions can kill within hours. Every minute counts.

What Comes Next

By 2027, 95% of high-altitude trekking companies will require a pre-trip medical consultation. Insurance companies are pushing for it. Liability is too high. You don’t have to wait for that change. Do it now. Talk to your doctor. Pack smart. Know your meds. Respect the mountain.This isn’t just about surviving a trek. It’s about honoring the purpose of your journey-whether it’s spiritual, physical, or personal. You’ve come too far to be stopped by something you could’ve prevented.

12 Comments

This is exactly what I needed to read before my trek next month 🙏 I was already packing my meds but now I’m doubling everything and sleeping with my insulin under my pillow 😅 You’re a lifesaver!

I appreciate how practical this is. No fluff. Just facts. I’ve seen too many people treat high altitude like a weekend hike. This should be mandatory reading for anyone booking a trek.

LMAO people still think they can just buy Diamox at some roadside stall in Nepal? Bro. The only thing they sell there are fake oxygen canisters and expired ibuprofen. I’ve seen it. People die because they’re too lazy to pack right.

Thank you for writing this with such care. This isn’t just advice-it’s a gift to anyone who’s ever felt the mountain calling but didn’t know how to answer safely. You’ve honored the journey. 🌄

Wait so if you’re diabetic and you’re flying into Lhasa, do you need to get your glucometer calibrated before you leave? Or just test it the first night? I’m paranoid now because mine gave me a weird reading in Colorado last year.

I think this whole article is just corporate fearmongering disguised as medical advice they want you to pay for. The mountain has been around for thousands of years and people survived without Dexamethasone. Why do we need all these pills now? Maybe we’re just weak. Maybe we should just suffer like our ancestors did. Or maybe you’re just selling supplements.

The fact that 89% of health camps don’t have acetazolamide is criminal. And yet somehow the same people who run those camps sell you $50 'altitude tea' that’s just ginger and sugar. We’ve turned survival into a tourist trap. 🤡

I’m Indian and I’ve done Kailash twice. This article is so American. We don’t need all this gear. We have faith. We have prayer flags. We have our ancestors watching over us. Why are you so scared? Why do you need a satellite device to talk to God?

The 2013 Nepal survey cited here is outdated. The 2021 WHO report shows 74% of major trekking clinics now stock essential meds. Also, you ignored the cultural context-many pilgrims use traditional remedies like Rhodiola rosea, which has comparable efficacy to acetazolamide in some studies. This is Western-centric medical colonialism.

I’m not even going to read all this. I just want to know: can I take my Adderall up there? My doctor said no but I’m already taking it daily and I don’t want to crash on the mountain. Also, is it weird that I brought my vape? Just asking.

You missed the most critical point: hypoxia-induced cerebral vasoconstriction alters CYP450 enzyme activity, which can significantly reduce the bioavailability of oral medications like acetazolamide and nifedipine. You need to account for pharmacokinetic shifts at altitude-not just dosage. Also, don’t forget the role of endothelin-1 in HAPE pathogenesis.

To the person asking about Adderall-please don’t. Your heart is already working overtime up there. Adderall + hypoxia = cardiac event waiting to happen. I’ve seen it. And no, your vape won’t help. Bring a book instead. And maybe some chocolate. 🍫

Write a comment