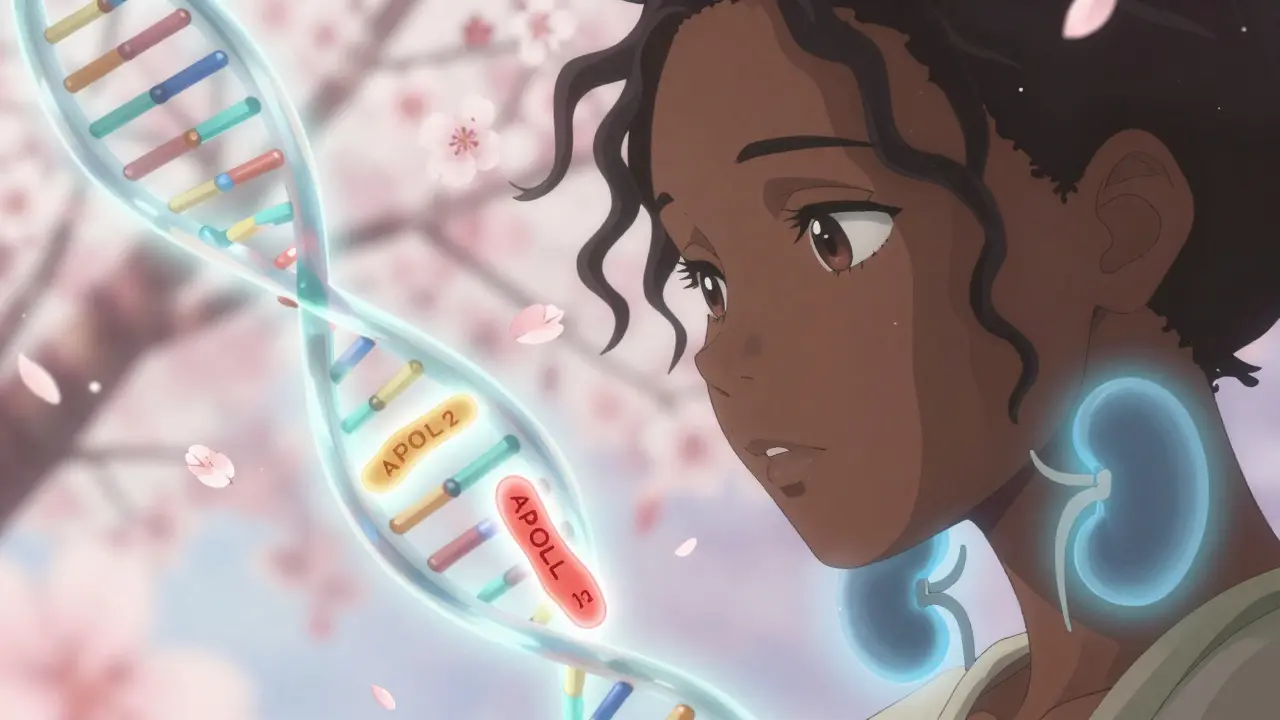

If you have recent African ancestry, your risk for certain types of kidney disease isn't just about lifestyle or blood pressure-it's written into your DNA. A single gene, APOL1, is responsible for nearly 70% of the extra kidney disease risk seen in people of African descent. This isn’t a general trend-it’s a powerful, specific genetic effect that explains why African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and others with recent West African roots are 3 to 4 times more likely to develop kidney failure than white Americans.

Why APOL1 Exists: An Evolutionary Trade-Off

The APOL1 gene didn’t evolve to cause kidney disease. It evolved to save lives. Around 5,000 to 10,000 years ago in West Africa, two mutations-G1 and G2-arose in the APOL1 gene. These changes made the protein better at killing Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, the parasite that causes African sleeping sickness. That deadly disease killed thousands, but people with these mutations survived and passed them on. Over generations, the mutations became common in populations where the parasite thrived.

Today, those same mutations can harm the kidneys. The APOL1 protein, designed to punch holes in parasites, sometimes does the same thing to kidney cells. When it misfires, it triggers inflammation and scarring. This is why APOL1-related kidney disease doesn’t show up in childhood-it usually strikes in adulthood, often after another trigger, like an infection or high blood pressure.

How APOL1 Risk Works: Two Copies, Not One

Unlike most inherited diseases, you need two bad copies of APOL1 to be at high risk. This is called a recessive pattern. You can carry one copy-many people do-and never have a problem. But if you inherit G1 or G2 from both parents, your risk jumps dramatically.

- Homozygous G1/G1: Two copies of the G1 variant

- Homozygous G2/G2: Two copies of the G2 variant

- Compound heterozygous G1/G2: One of each

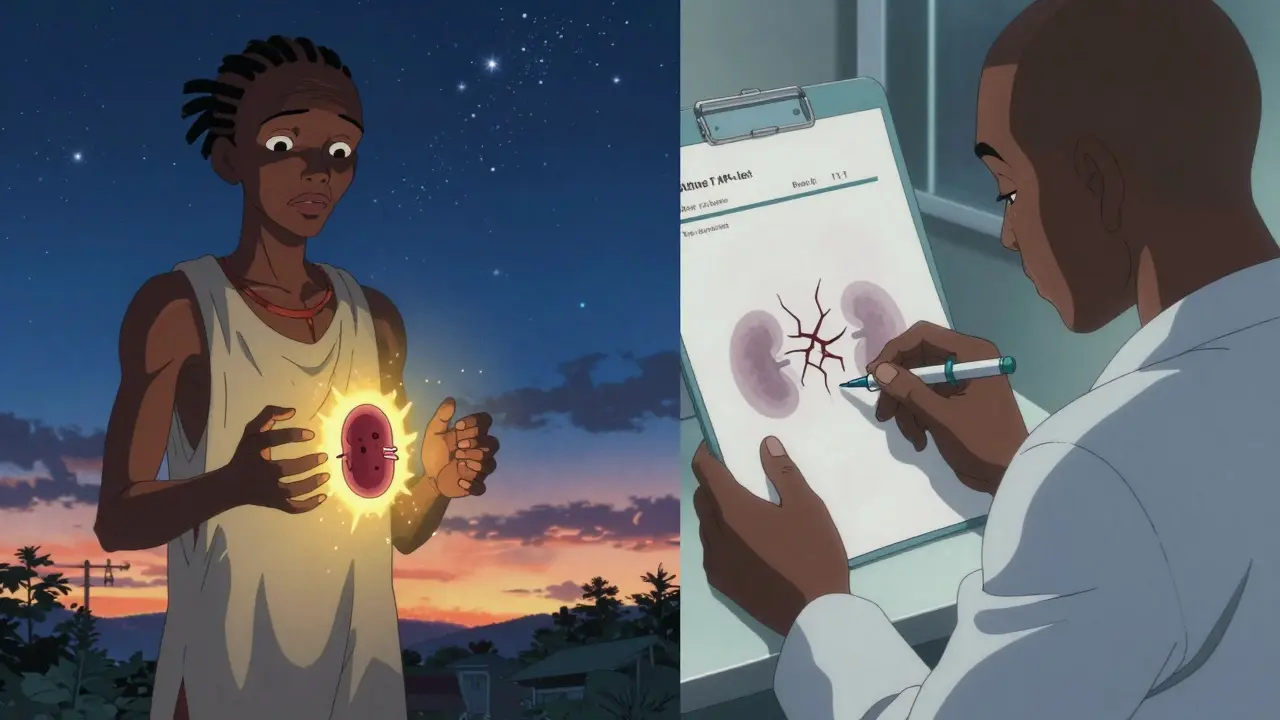

These three combinations are called high-risk genotypes. About 13% of African Americans have them. But here’s the twist: 70% of people with these genotypes never develop kidney disease. That means something else-like HIV, obesity, or uncontrolled blood pressure-has to push the system over the edge. Scientists call these "second hits." Without them, the gene alone often stays quiet.

What Kidney Diseases Does APOL1 Cause?

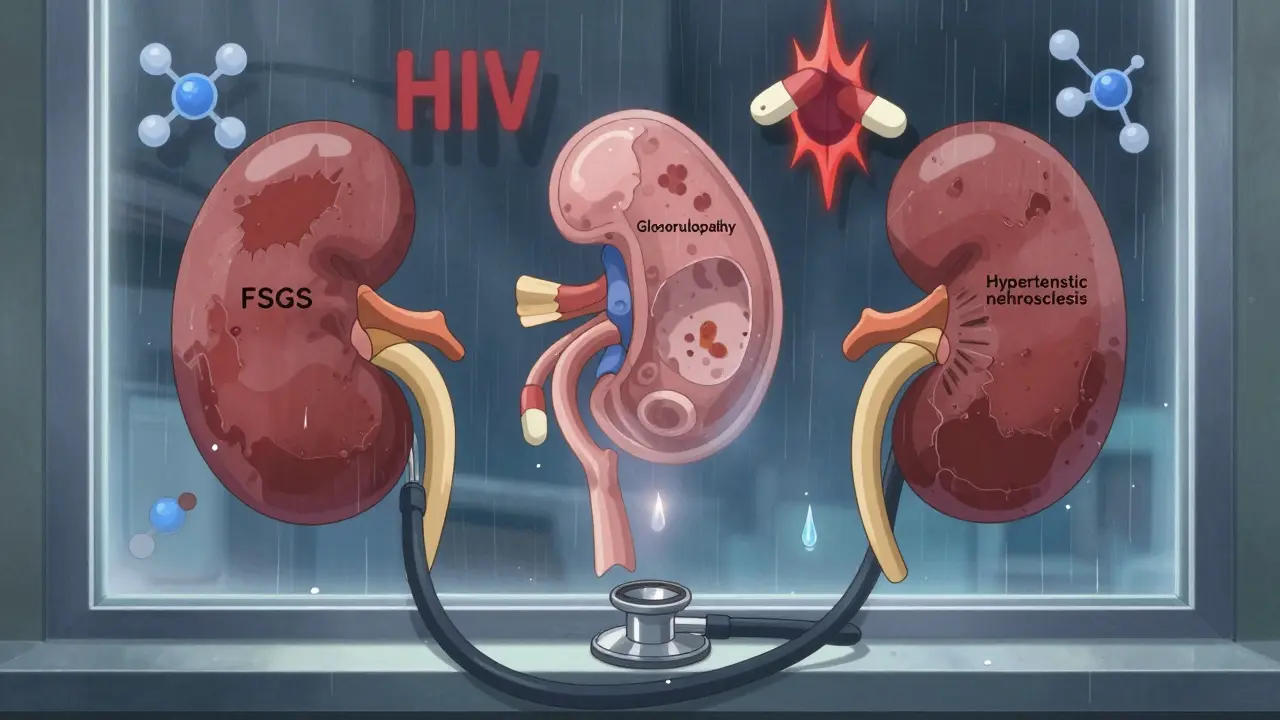

APOL1 doesn’t cause one type of kidney disease-it causes several, all linked by similar damage patterns:

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS): Scarring in the kidney’s filtering units. APOL1 is the most common genetic cause in African ancestry populations.

- Collapsing glomerulopathy: A severe form of kidney damage often seen in people with HIV. In the UK, nearly half of all HIV-related kidney failure in Black patients was tied to APOL1.

- Hypertensive nephrosclerosis: Kidney damage from high blood pressure. APOL1 makes the kidneys far more vulnerable to this damage.

These aren’t rare conditions. In African Americans with non-diabetic kidney failure, about half carry high-risk APOL1 variants. That’s not coincidence-it’s the root cause.

Testing for APOL1: Who Should Get It?

Genetic testing for APOL1 became available in 2016. It’s not for everyone-but it’s critical for some.

Testing is recommended for:

- People of African ancestry with unexplained kidney disease (especially FSGS or collapsing glomerulopathy)

- Living kidney donors with African ancestry (to protect their own health)

- People with HIV and kidney damage

The test costs between $250 and $450 without insurance. Many insurance plans now cover it if there’s a clinical reason. Results come back in about 7 to 14 days. But knowing your status isn’t just about diagnosis-it’s about prevention.

What to Do If You Have High-Risk APOL1

Having the high-risk genotype doesn’t mean you’ll get kidney failure. It means you need to be extra careful. The goal isn’t to panic-it’s to protect.

Three key steps:

- Control blood pressure: Aim for under 130/80 mmHg. ACE inhibitors or ARBs are often first-line-they reduce protein leakage and protect kidney cells.

- Test urine yearly: The urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) catches early kidney damage before blood tests show it. Even small amounts of protein in urine matter.

- Avoid triggers: Don’t smoke. Manage diabetes. Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen if possible. Stay away from untreated HIV or other infections.

One patient, Emani, found out she had high-risk APOL1 before any damage occurred. She started monitoring her blood pressure and urine, changed her diet, and saw her kidney function stay stable for over five years. Knowledge gave her control.

The Bigger Picture: Race vs. Ancestry

APOL1 risk is not about "race." It’s about ancestry. The variants are common in people with recent roots in West Africa-not because of skin color, but because of shared genetic history. This distinction matters.

Doctors used to assume Black patients had worse kidney function just because of race. They adjusted kidney tests using race-based formulas. But APOL1 research showed that’s wrong. A Black person with no APOL1 risk variants may have perfectly normal kidney function. A white person with West African ancestry might carry the risk. That’s why the American Society of Nephrology and the FDA now push for genetic, not racial, markers in medical decisions.

As Dr. Olugbenga Gbadegesin put it: "We must be careful not to conflate social constructs of race with genetic ancestry."

What’s Next? New Treatments on the Horizon

For decades, there was no treatment for APOL1 kidney disease. Now, that’s changing.

In October 2023, Vertex Pharmaceuticals reported early success with a drug called VX-147. In a trial of 140 patients, it cut protein in the urine by 37% in just 13 weeks. That’s a major sign it’s protecting kidney cells. Phase 3 trials are underway.

The NIH has launched the APOL1 Observational Study (AOS), tracking 5,000 people with high-risk genotypes over 10 years. This will help predict who’s most likely to develop disease-and why.

By 2035, experts believe APOL1-targeted drugs could reduce kidney failure rates in African ancestry populations by 25% to 35%. But only if access is fair. Right now, only 12% of low- and middle-income countries offer APOL1 testing. That’s a crisis.

Living with the Knowledge

For some, finding out they have high-risk APOL1 is terrifying. "I was told I have a 1 in 5 chance of kidney failure," one patient wrote online. "The uncertainty is worse than a diagnosis."

But for others, it’s empowering. A medical student with the genotype now checks her blood pressure weekly. She gets her urine tested every year. She doesn’t live in fear-she lives with awareness.

APOL1 doesn’t define your future. But understanding it gives you power over it. You can’t change your genes. But you can change how you protect your kidneys.

Is APOL1 testing covered by insurance?

Yes, in many cases. Insurance often covers APOL1 testing if you have unexplained kidney disease, are being evaluated as a living kidney donor, or have HIV-related kidney damage. Out-of-pocket costs range from $250 to $450. Always ask your nephrologist or genetic counselor about coverage options.

Can I pass APOL1 risk to my children?

Yes. APOL1 follows an autosomal recessive pattern. If you have two risk variants, each child has a 100% chance of inheriting at least one copy. If your partner also carries a risk variant, there’s a 25% chance your child will inherit two copies and be at high risk. Genetic counseling is recommended before having children if you know your status.

Do I need to tell my employer or insurance company about my APOL1 status?

No. In the U.S., the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008 prohibits health insurers and employers from using genetic information to deny coverage or employment. APOL1 results are protected under GINA. However, life insurance and long-term care insurance are not covered by GINA, so disclosure rules vary.

Why don’t all people with APOL1 risk get kidney disease?

Only about 15-20% of people with high-risk APOL1 genotypes develop kidney disease. The rest have "incomplete penetrance." This means other factors-like viral infections (especially HIV), obesity, high blood pressure, or environmental toxins-act as "second hits" that trigger damage. Without these, the gene often stays dormant.

Is APOL1 testing available outside the U.S.?

Yes, but access is limited. Testing is available in the UK, Canada, and parts of Western Europe through specialized labs. In low- and middle-income countries, especially in Africa, testing is rarely available due to cost and infrastructure. The Global Kidney Health Atlas found only 12% of these countries offer APOL1 testing as of 2023.