When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the race to sell the first generic version begins. But here’s the twist: the company that made the original drug might launch its own generic version at the exact same time. And that changes everything.

What’s the difference between a first generic and an authorized generic?

A first generic is the very first company to successfully challenge a brand-name drug’s patent and get FDA approval to sell a generic version. This company gets a special reward: 180 days of exclusive rights to sell that generic, with no other generic competitors allowed. During that time, they often capture 80% or more of the market. It’s a big deal - if the drug is a blockbuster, that exclusivity can mean hundreds of millions in revenue.

An authorized generic is different. It’s made by the brand-name company itself - or by a partner they’ve authorized - using the same factory, same ingredients, same packaging as the original drug. But instead of selling it under the brand name, they slap a generic label on it and sell it for less. No new FDA application is needed. It’s essentially the brand-name drug in disguise.

The key difference? Timing. First generics have to wait months - sometimes years - to get FDA approval. Authorized generics can launch overnight.

Why does timing matter so much?

The whole point of the 180-day exclusivity rule, written into the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, was to encourage generic companies to take on the legal and financial risk of challenging patents. The idea was simple: reward the first challenger with a monopoly, and that will drive down prices faster for everyone.

But here’s what happened in practice: brand-name companies figured out how to game the system. They started launching their own authorized generics the same day or within weeks of the first generic hitting the market. Suddenly, instead of having the market to themselves, the first generic is now competing with a product that’s identical to the brand - but cheaper.

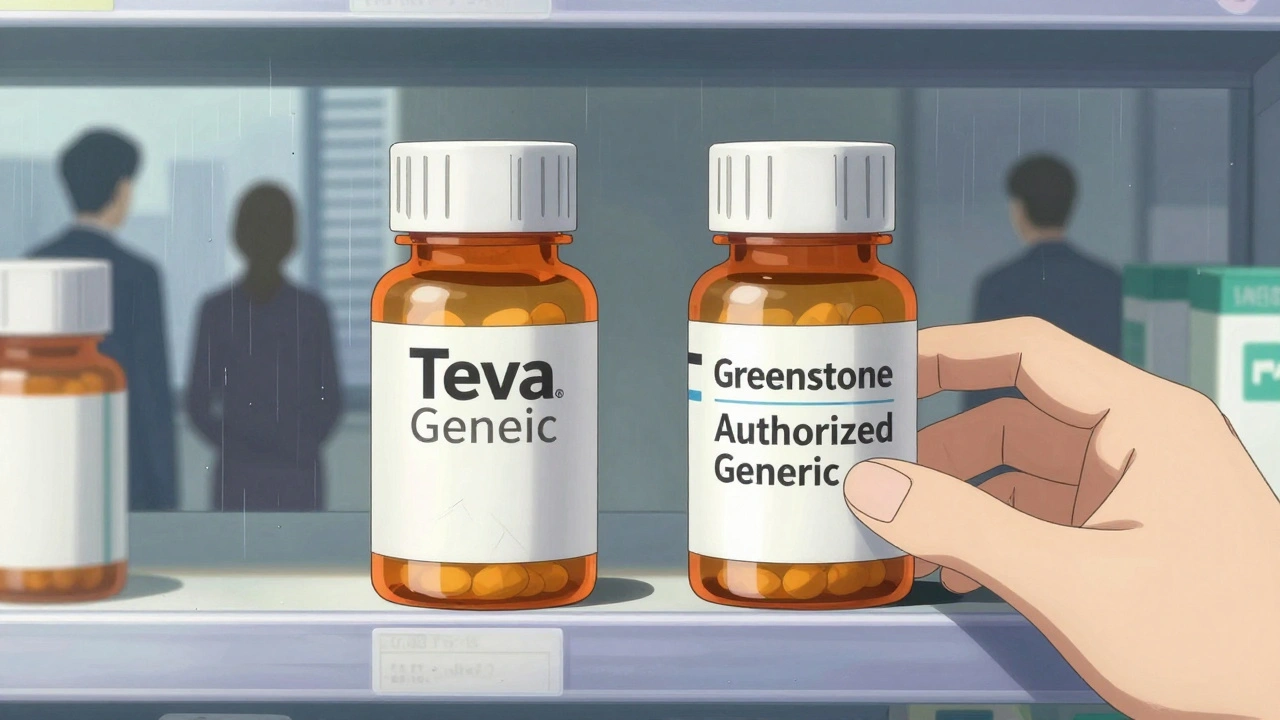

Take Lyrica (pregabalin). When Teva launched the first generic in July 2019, Pfizer immediately rolled out its own authorized generic through Greenstone LLC. Within weeks, Pfizer’s version captured about 30% of the market. Teva’s expected revenue during its 180-day window dropped by nearly half. That’s not competition - that’s sabotage.

Research from Health Affairs shows that 73% of authorized generics launched within 90 days of the first generic’s approval. Over 40% launched on the exact same day. This isn’t coincidence. It’s strategy.

How does this affect drug prices?

Generic drugs usually cut prices by 80-90%. That’s the promise. But when an authorized generic enters during the first generic’s exclusivity period, the price drop slows to just 65-75%.

Why? Because now there are two generic options - but neither has full control. The first generic can’t raise prices because the authorized generic is right there. The authorized generic can’t drop prices too far because it’s still tied to the brand’s profit margins. The result? Prices stay higher than they should, and patients and insurers pay more.

The RAND Corporation estimated this tactic costs the U.S. healthcare system billions each year. Imagine a drug that should cost $10 a month - but instead stays at $35 because two generics are fighting over a shrinking pie.

Which drugs are most affected?

This isn’t happening with every drug. It’s concentrated in high-revenue, high-demand medications.

- Cardiovascular drugs (32% of cases) - think blood pressure and cholesterol meds

- Central nervous system drugs (24%) - like gabapentin, pregabalin, and antidepressants

- Metabolic disorders (18%) - diabetes drugs like empagliflozin (Jardiance)

Drugs like Eliquis (apixaban) and Jardiance are current battlegrounds. Brand companies are already preparing their authorized generic launch plans before the first generic even gets approved.

How do companies respond?

Generic manufacturers aren’t sitting still. Many now treat authorized generics as a guaranteed risk - not an outlier.

Leading firms are shifting strategies:

- They’re building faster approval pipelines to get into the market even quicker

- They’re diversifying their portfolios so they don’t rely on one blockbuster generic

- They’re filing patent challenges on multiple drugs at once, spreading out the risk

Executives at mid-sized generic companies say the profitable window for first generics has shrunk from 180 days to just 45-60 days in many categories. That’s not a business model - that’s a survival tactic.

What’s the regulatory response?

The FDA still approves around 80 first generics a year, but the process is slow. Under GDUFA, the average review takes 10 months - but backlogs in the past pushed it to over three years.

Meanwhile, authorized generics skip the line entirely. They use the brand’s existing NDA, not a new ANDA. No bioequivalence studies. No delays. Just a label change and a price drop.

In 2022, Congress took a stand. The Inflation Reduction Act explicitly said authorized generics aren’t considered true generic competitors when it comes to Medicare drug price negotiations. That’s a rare moment of clarity - lawmakers recognized that these aren’t the same as independent generics.

The FTC has also taken action against "pay-for-delay" deals, where brand companies pay generics to delay entry. But enforcement is patchy. And authorized generics? They’re legal. They’re transparent. And they’re devastatingly effective.

What’s the future?

By 2027, authorized generics are expected to make up 25-30% of all generic prescriptions - up from 18% in 2022. That’s not growth. That’s a transformation.

The original goal of Hatch-Waxman - to get cheap generics to market fast - is being undermined by the very system meant to support it. The first generic isn’t the pioneer anymore. It’s the bait.

For patients, the outcome is mixed. Yes, there are more generic options. But prices aren’t falling as hard or as fast as they should. For insurers and taxpayers, it means higher costs. For generic manufacturers, it means higher risk and lower rewards.

The system was designed to reward courage. Now, it rewards timing - and the brand companies have the best clock.

What should patients and prescribers know?

If you’re on a brand-name drug that’s going generic, don’t assume the cheapest option is the "real" generic. Check the label. Is it made by the brand company? If so, it’s an authorized generic. It’s just as safe. But it’s not the same as the independent generic that fought the patent.

Ask your pharmacist: "Is this an authorized generic?" It’s a simple question - and it might help you understand why your copay isn’t lower than expected.

And if you’re part of a health plan that negotiates drug prices, ask: "Are we accounting for authorized generics in our savings estimates?" Because if you’re not, you’re overpaying.

10 Comments

So let me get this straight - the system was designed to punish monopolies but now the monopolists just invented a new kind of monopoly that’s LEGAL? Genius. Absolute genius. They didn’t break the rules, they just rewrote the game while everyone else was still playing checkers. And we wonder why healthcare costs are insane. This isn’t capitalism. This is corporate cannibalism with a FDA stamp on it.

This is actually really heartbreaking. I’ve seen friends choose between their meds and rent because the 'generic' they were promised still cost too much. It’s not just about profits - it’s about people being told they’re getting relief, but the relief is fake. The system pretends to help, but it’s rigged from the start. I just hope someone with real power reads this and feels ashamed.

So the brand company just makes a generic version of their own drug? Like… they’re not even trying to hide it? Lmao. I just ordered my pregabalin and it says ‘Greenstone’ on the bottle. Google it - it’s Pfizer. So yeah, I’m literally taking the brand drug but paying less. And still not enough. The system is a joke.

First generic gets 180 days? LOL. That’s a fairy tale. The real rule is: whoever has the most lawyers wins. And the big pharma boys have entire armies. The FDA? They’re asleep at the wheel. This isn’t healthcare - it’s Wall Street with a stethoscope. Fix it or shut it down.

Okay but hear me out - what if we flipped the script? What if we rewarded the brand companies for launching authorized generics early? Like, give them tax breaks or faster approval on their next drug if they help drop prices fast? Maybe the problem isn’t the tactic - it’s the punishment model. We need incentives, not just outrage. Let’s build a better system, not just scream at the old one.

The structural irony here is almost poetic: the Hatch-Waxman Act was conceived as a mechanism to democratize access to essential medicines by incentivizing patent challenges, yet the very architecture of the system has been subverted by the incumbents who possess the regulatory capital to deploy authorized generics without the burden of new ANDA submissions. The result is a market distortion wherein the legal and financial risk borne by independent generics is systematically neutralized by the incumbent’s ability to preemptively flood the market with a product that is functionally indistinguishable from the branded version, thereby undermining the intended economic incentive structure. This is not market competition - it is regulatory arbitrage dressed as innovation.

Y’all need to stop acting like this is new. This has been happening since the 2000s. I work in pharmacy and we’ve been telling patients for years: ‘That generic? Yeah, same pill, different label, same company.’ But no one listens until the copay doesn’t drop. Honestly? Just ask for the independent generic. It’s usually cheaper anyway. And if your pharmacist looks confused? That’s your sign to dig deeper.

so the brand company makes a generic of their own drug... and we're all supposed to be shocked? 😂 like, did anyone think they wouldn't do this? the whole system is designed to let them win. we're just mad because they didn't even bother to pretend anymore.

lol imagine being the first generic company and thinking you won… only to find out the brand just dropped a clone on you with the same factory and same logo except smaller. 🤡 i feel bad for the little guys but also… they should’ve seen this coming. maybe next time don’t trust a system built by the people you’re trying to beat.

What if the real problem isn’t authorized generics… but the fact that we let corporations write healthcare policy? The FDA isn’t broken - it’s a tool. And right now, it’s being used to protect profit, not people. We don’t need more loopholes. We need to dismantle the idea that medicine should be a commodity. This isn’t about timing. It’s about morality. And right now, we’ve lost that battle. But we can still win the war - if we stop treating patients like balance sheet entries.

Write a comment